I took part in a panel discussion on contemporary drawing other day with fellow NEAC painters Paul Newland, Toby Ward and Ben Hughes on why we draw, below is an edited version of my talk:

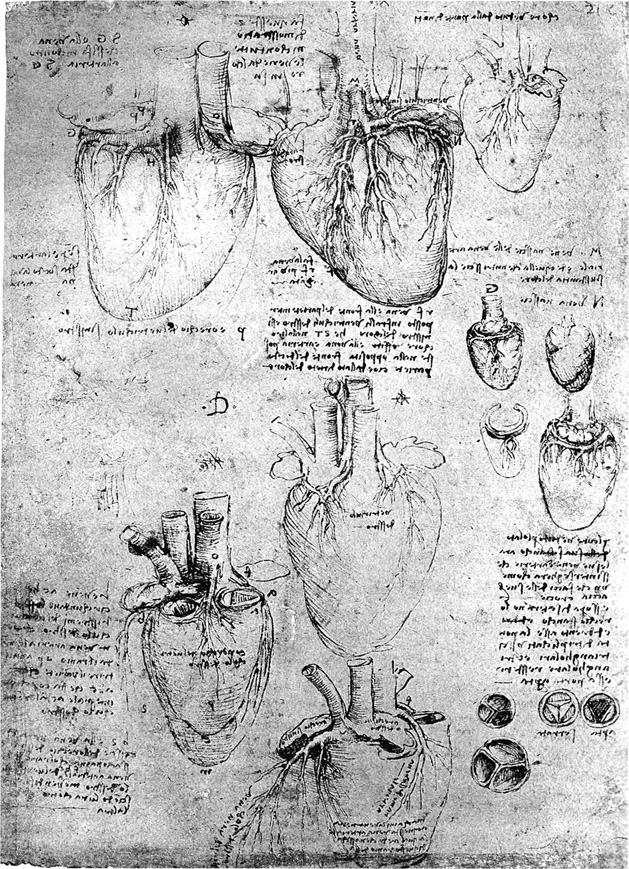

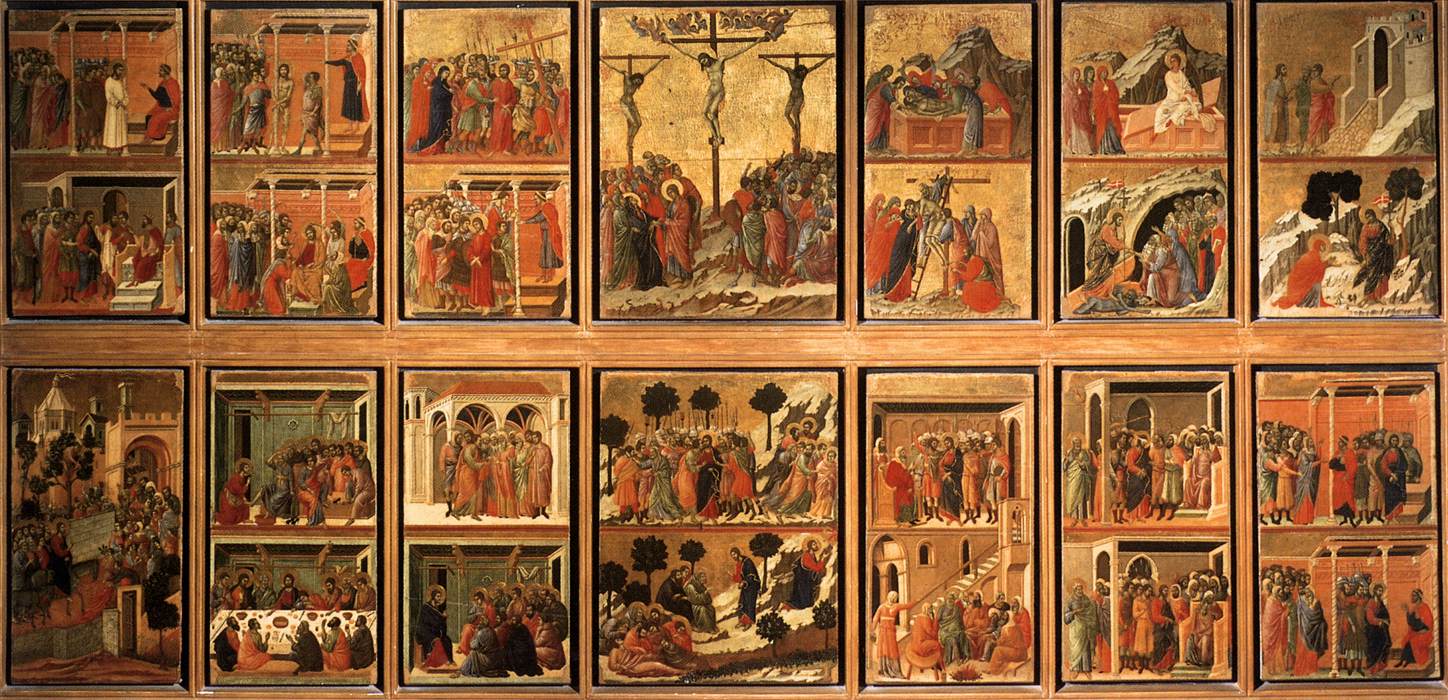

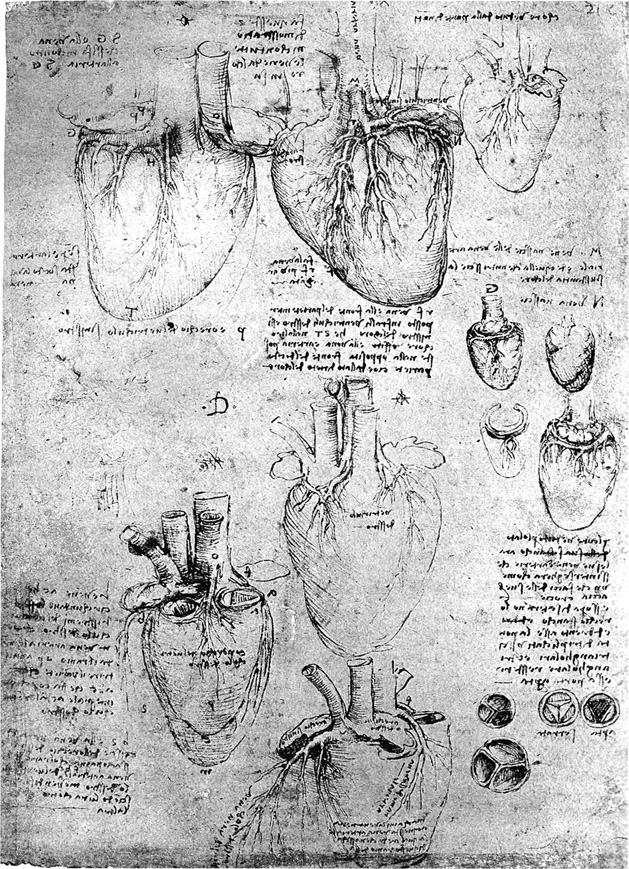

A while ago Andrew Graham Dixon gave a robust argument for drawing skills on Radio 4’s Start The Week: He told the story of a famous heart surgeon who insisted that his students draw the structure of the heart ventricles from life in the dissection room to get to grips with the overall make up of the heart. In the surgeon’s view no amount of passive looking would enable an understanding as thorough as the challenge of having to explain the heart’s three dimensional structure in two dimensions.

Here is Leonardo Da Vinci’s drawing of a human heart which demonstrates Andrew’s point perfectly..

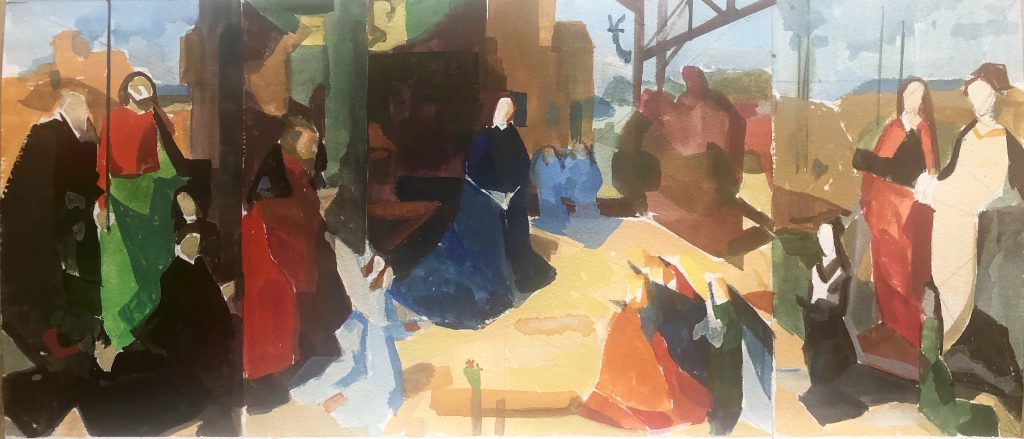

Some painters manage to think directly in paint, but drawing is how I get to understand what I see and is fundamental to making my paintings. I think of my work as a two stage process, the empirical, observational part that takes place through drawing when I start to discover a new subject, and the synthetic compositional part that happens later on in the studio armed with my paint brush, often collaging together different drawing elements.

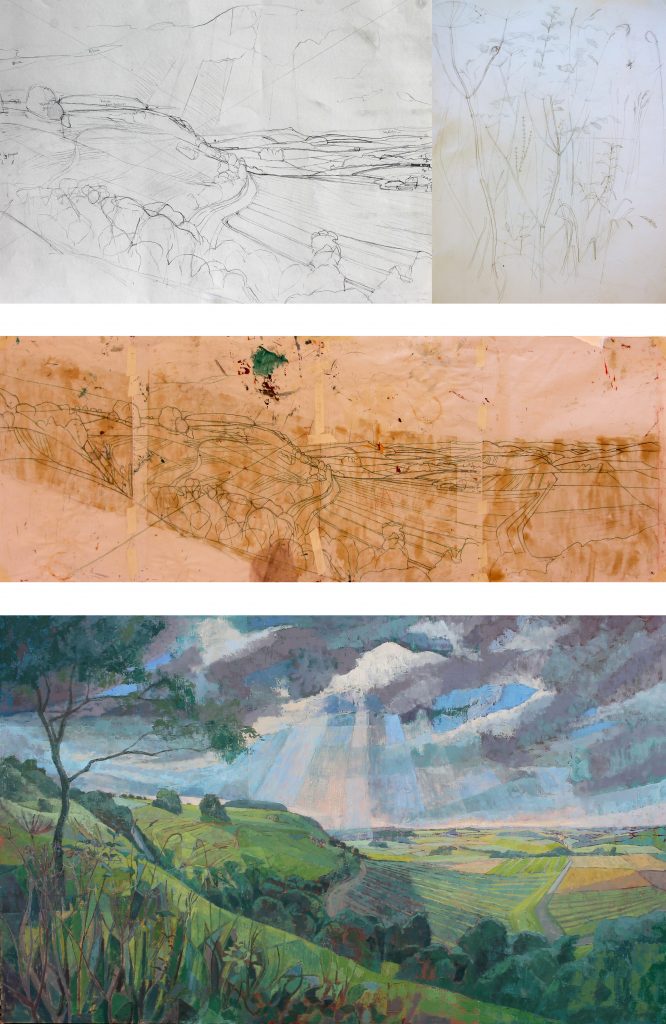

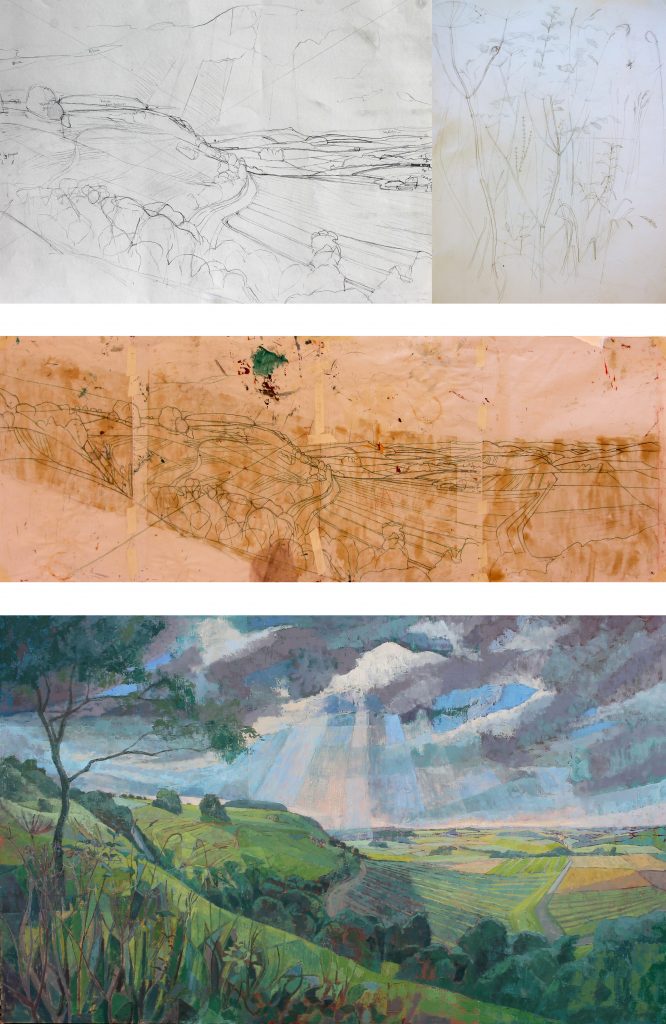

This slide of a large landscape painting I did last year shows this progression: I spent a couple of days drawing on the side of a rather windswept hill down in Dorset, jotting down colour notes and light direction to give me an idea of ground and palette I wanted to capture the autumnal air, and the spectacular late afternoon stormy skies that happened on the first day.

When I got back to the studio I made scaled up cartoons from the drawings and transferred them to a large board and started to paint. By this stage I know the palette I’m going to use based on the light conditions, weather and atmosphere I want to capture. Its always a limited palette but can vary enormously according to the requirements of the subject. With this painting I used a pretty deep intense set of colours to capture the brooding skies and heavy atmosphere: Indian Red, Viridian Green, Cereleum Blue Deep, Yellow Ochre and Lemon Yellow. Later on I returned outdoors for some hedgerow detail which was added into the foreground once I had worked out the overall composition.

My drawing priorities are capturing a sense of the space I’m thinking about, usually bending perspective rules a little, using instead relative scale, shapes, internal structure, tone, the fall of light and overall composition of a subject. If I have grasped these qualities I can get started on a painting back in the studio armed with my drawings. As my work is about creating space and light with colour I’m not particularly interested in surface texture and small detail, so these tend to go unremarked on whilst drawing.

Often my subject matter presents itself because of unusual and compelling colour relationships and shapes. That’s the missing piece of the compositional jigsaw in drawing, but I can capture a lot of colour ideas by carefully studying tonal relationships.

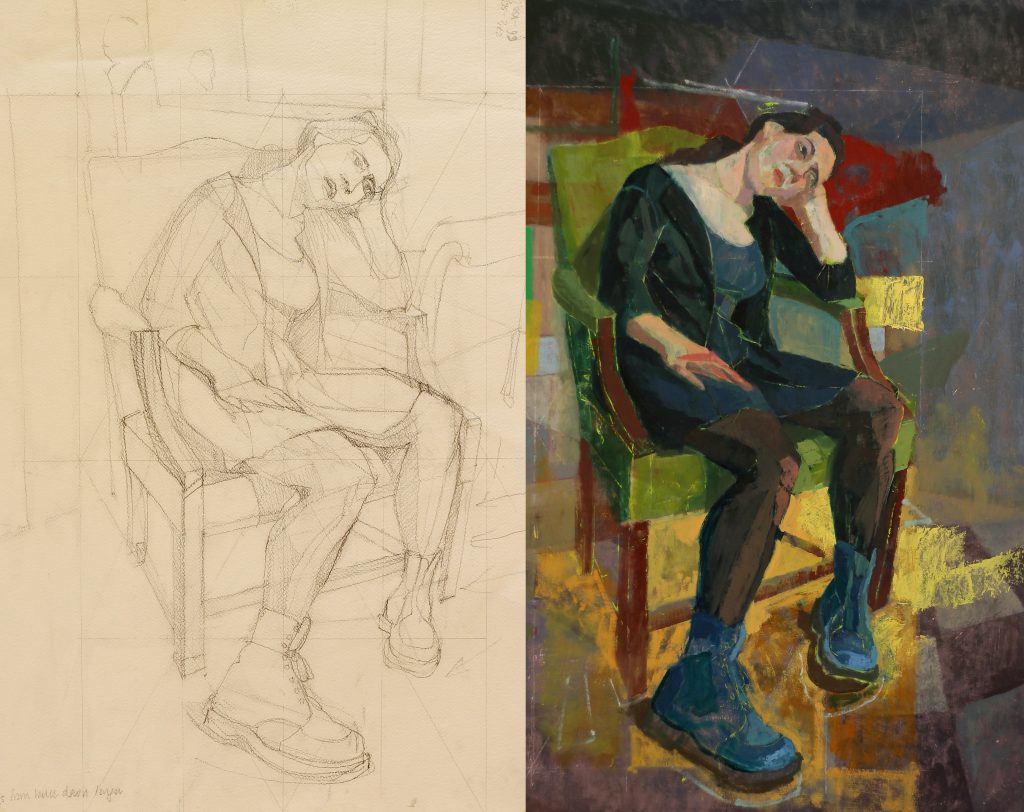

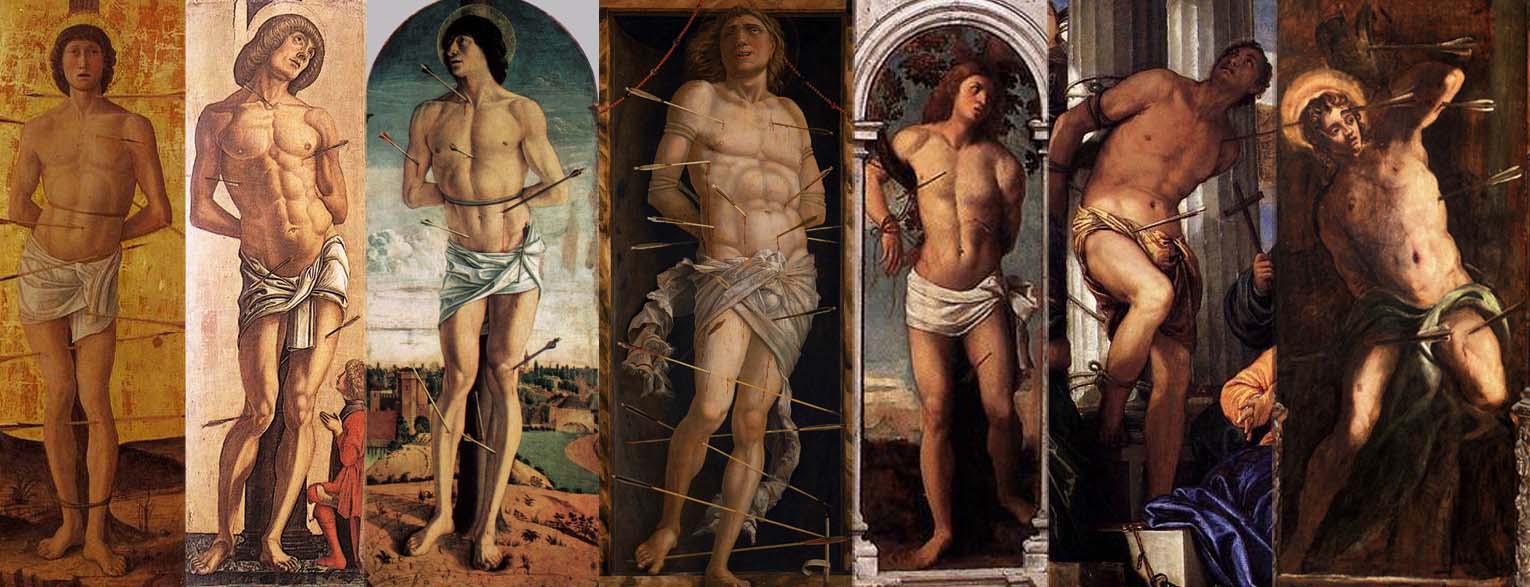

This drawing from a life class that I go to regularly is the kind of tonal approach that I can use as a starting point for a painting.

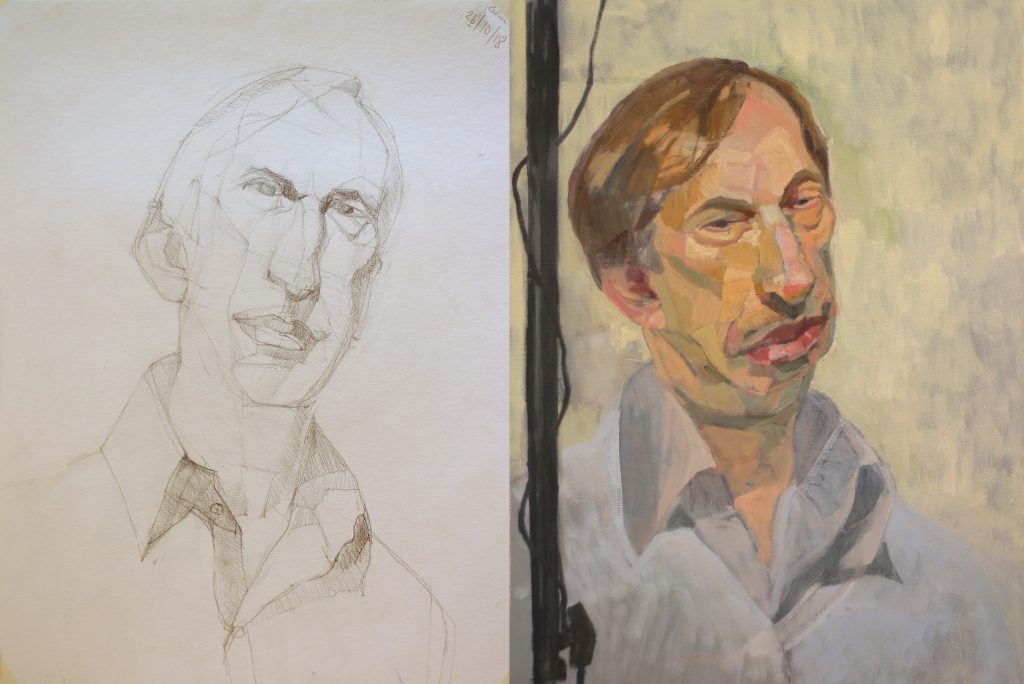

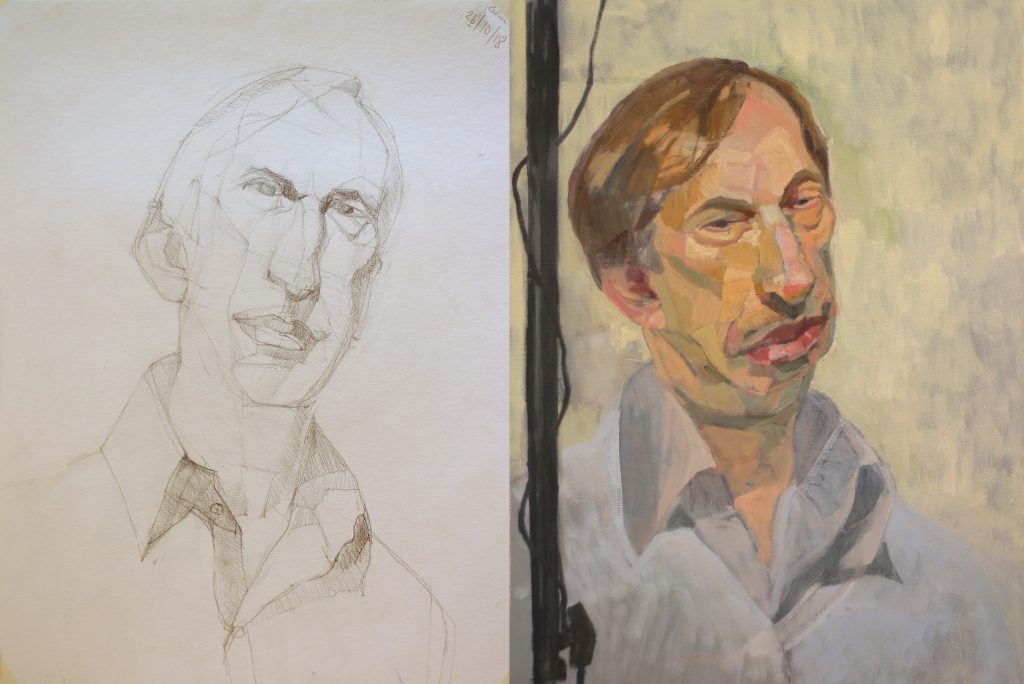

Thinking a little about contours and edges: I find a drawing always benefits when I stop thinking in terms of labels: mouth, eyeball, etc and instead think in an abstract way: negative shapes, contours turning into inside edges, making sense of a contour by following internal structure -that sort of thing.

This portrait drawing I hope demonstrates this sort of approach. Although Robin’s pose changed between these two works, I found the painting much easier to tackle as I had already worked out what was going on with his unusual jaw and chin in the drawing.

I always try and make my drawings by as simple means as possible, I think big to small, and don’t worry about unnecessary detail. If the overall structure doesn’t work, no amount of clutter will cover that lack of understanding. I always have at the back of my mind: is this information essential to start a painting without direct reference to the subject?

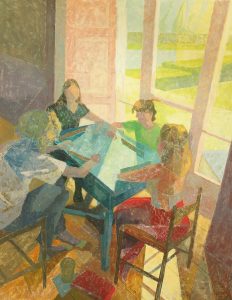

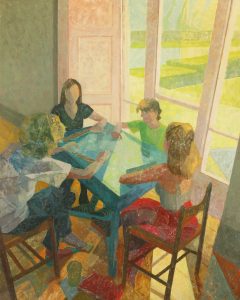

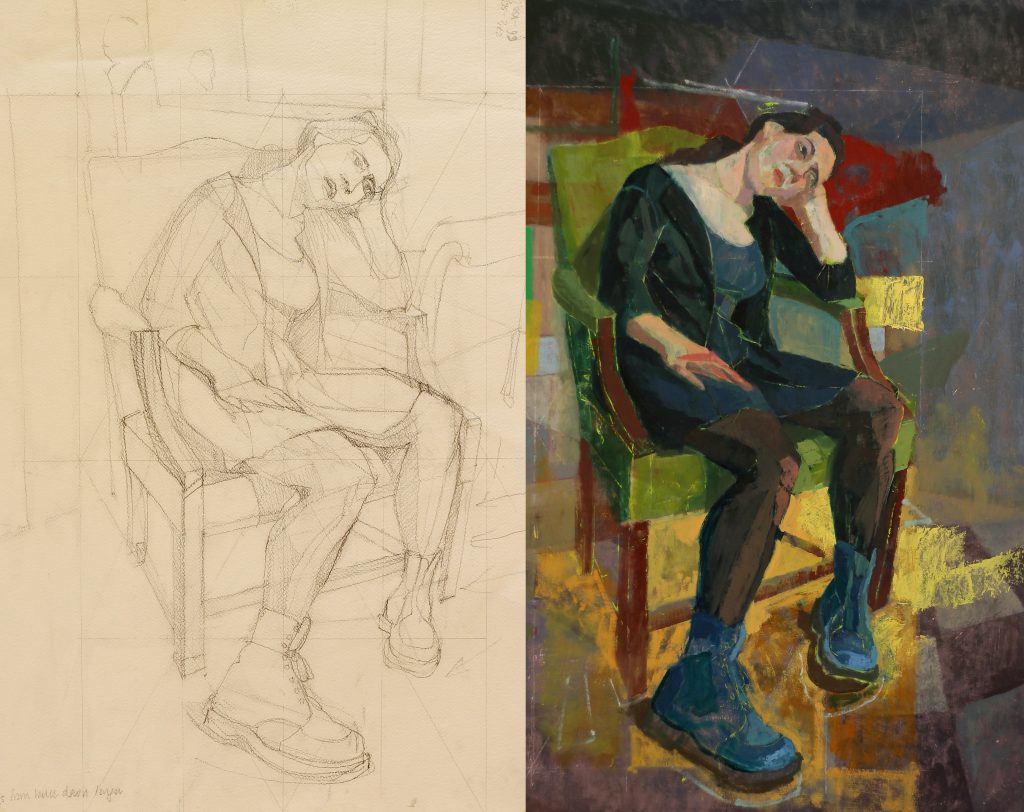

Here’s a couple of stabs at capturing Alice that went badly wrong, I didn’t work out her proportions properly in the drawing, so when I started the painting later I got myself in a pickle over her arms and the twist in her torso. I’m still pondering what to do about this one as Alice has now returned to France.

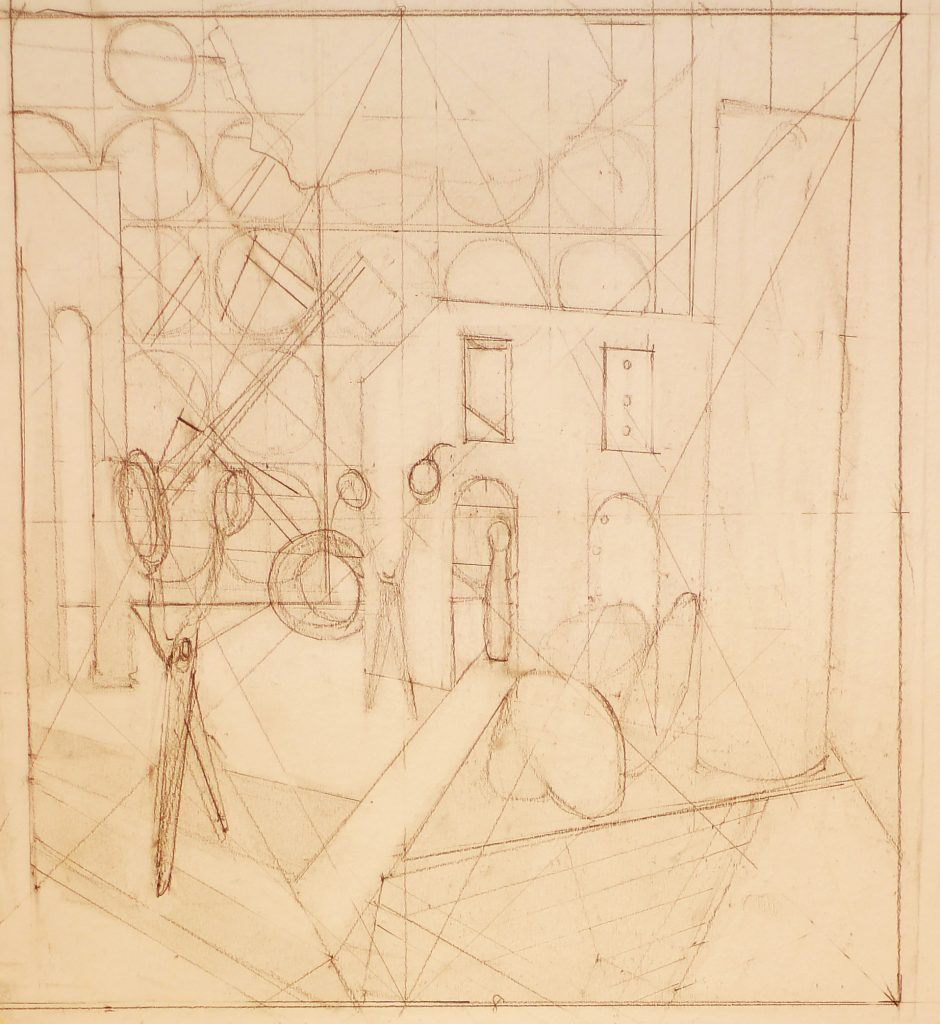

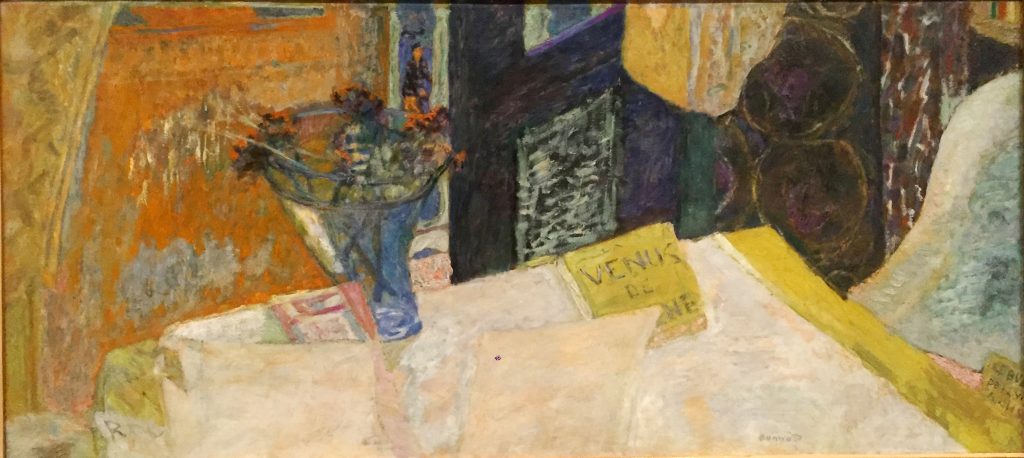

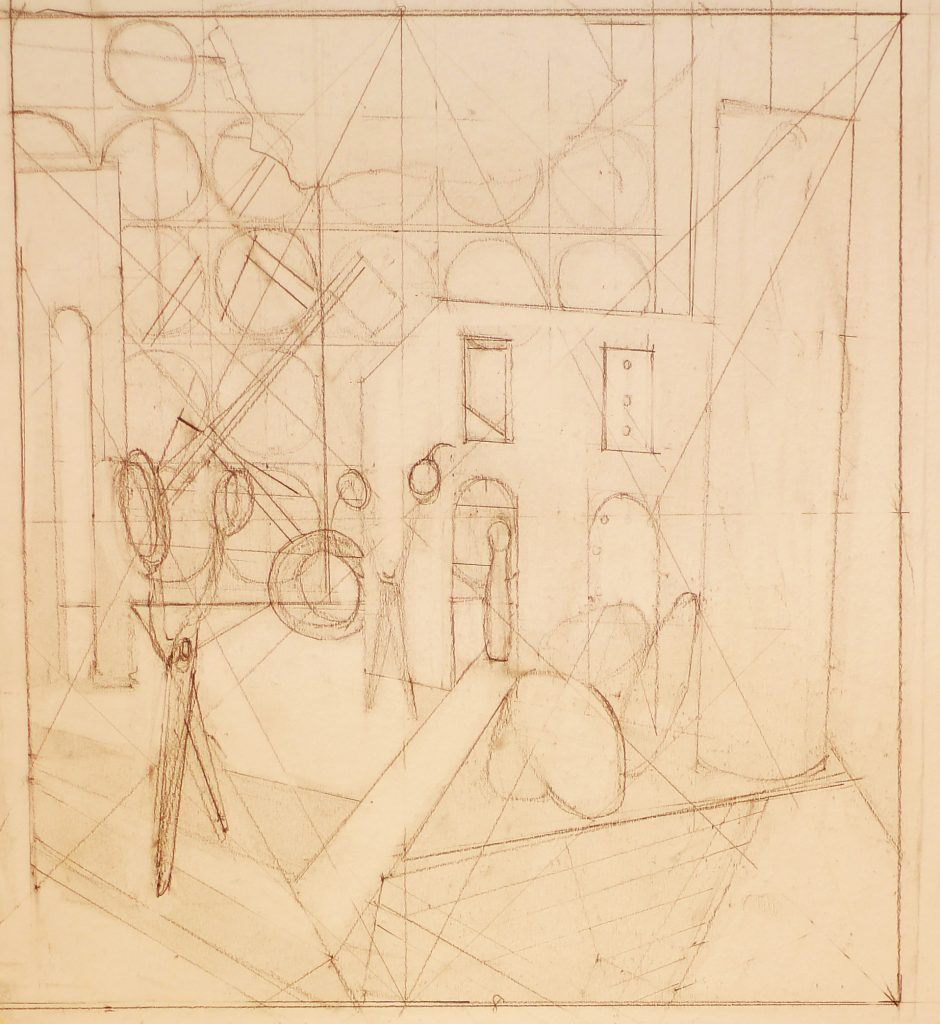

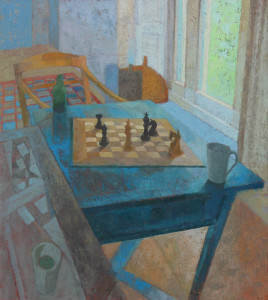

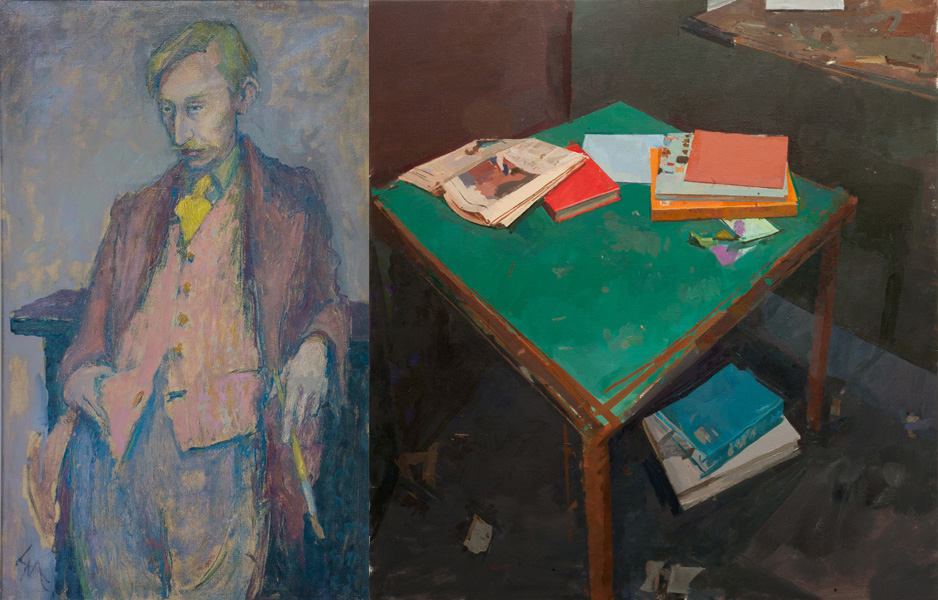

Finally here is the compositional drawing for ‘Rock Paper Scissors’, one of the paintings in this exhibition. I followed this drawing pretty closely in the painting as the work was all about clean crisp edges and the fall of light and on a much smaller scale than my normal work, so less room for manouvre.